Description

The Portuguese Communist Party is one of the largest in the world (when compared to the size of the country’s population), certainly in the capitalist world. It must have come as something of a surprise for Portuguese readers to learn that its longtime leader, Alvaro Cunhal, had made a sideline career for himself as a Neo-realist, fiction writer. Five Days, Five Nights is his first book to appear in English. International Publishers, renowned for its historic catalogue of publications of non-fiction, including Marxist theoretical studies, fiction, memoir and poetry, is proud to present this unusual novella as a long overdue expression of gratitude for Alvaro Cunhal’s self sacrificing leadership of the Portuguese Communists during most of the half-century of fascism in his land.

Stylistically, Five Days, Five Nights approximates something of the 1940s and ’50s noir writers’ and filmmakers’ hyper-realist sensibilities, though any direct influence on the writer is not likely, for Cunhal wrote this book while imprisoned in Portugal. He was able to slip it past the censors, who saw little specifically political in it, merely the story of an emigrant escaping the country, a common occurrence at the time. Notably, there is no reference to the Party as such, though readers are welcome to infer its presence in the background.

The manuscript of this novella was found in the archives of the Forte de Peniche, where Cunhal had been imprisoned. Cunhal had left it behind when he escaped on January 3, 1960, although he did take with him the manuscript to another, much longer and more specifically political novel, Até Amanhã, Camaradas. After the 25th of April 1974 Revolution that brought an end to fascism in Portugal, the military officers in charge of the fort returned the manuscript to Cunhal, and he published it in 1975 under the pseudonym Manuel Tiago, with a fictitious indication that it had been found in the “author’s” papers after his death (an explanation he also used for Até Amanhã, Camaradas). At the time the true authorship of these books was known only to the Party leadership. Only later in life, in 1994, did Cunhal acknowledge that he was “Manuel Tiago,” pseudonymous author of several books.

Estado Novo or— “New State” was a version of fascism and a setting of the story in the early 1930s would seem probable. Furthermore, it seems to predate the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) and Francisco Franco’s subsequent fascist regime, if we are to accept the logic of an escape over the border from the oppressive Portugal to an untroubled Spain as described in the book. However, If we understand the story as existing outside of a specific time, involving archetypal situations, relationships and circumstances, then to that extent it achieves a certain universality, standing in for similar, parallel conditions almost anywhere in the world at any time.

In the final analysis, Five Days, Five Nights was written to remind readers not only of the sacrifices made by fascism’s resisters, but of the loss of creativity and intelligence that Portugal suffered due to fascism’s erosion of talented, hardworking citizens.

Barbara T. Russum –

Beautifully translated by Eric A. Gordon.

Eric A. Gordon is the author of a biography of radical American composer Marc Blitzstein, co-author of composer Earl Robinson’s autobiography, and the translator (from Portuguese) of a memoir by Brazilian author Hadasa Cytrynowicz. He holds a doctorate in history from Tulane University. He chaired the Southern California chapter of the National Writers Union, Local 1981 UAW (AFL-CIO) for two terms and is director emeritus of The Workmen’s Circle/Arbeter Ring Southern California District. In 2015 he produced “City of the Future,” a CD of Soviet Yiddish songs by Samuel Polonski. He received the Better Lemons “Up Late” Critic Award for 2019, awarded to the most prolific critic.

Barbara T. Russum –

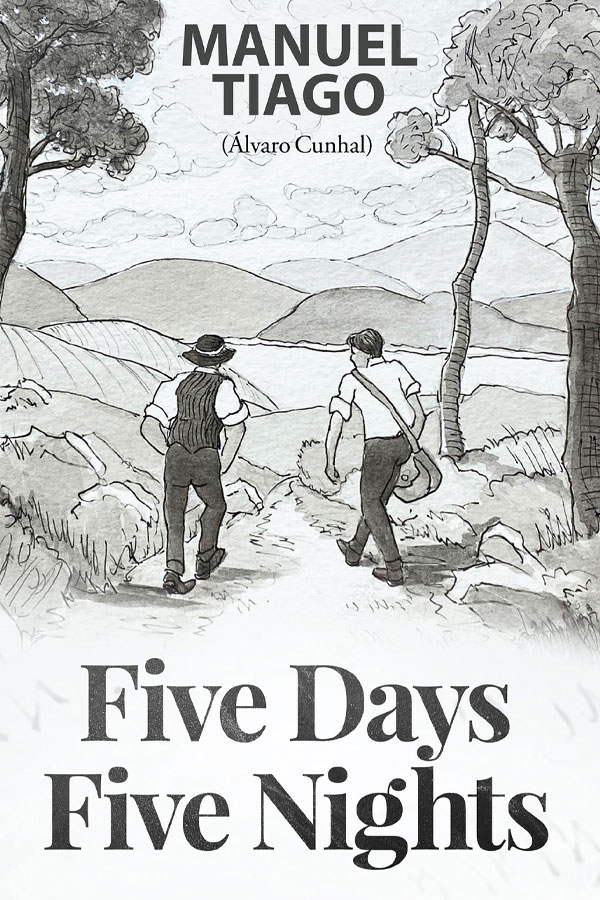

About the Illustrator

Artist Ilse Gordon lives in Cos Cob, Connecticut, where she is known for her local landscapes of public parks and private gardens. A graduate of Sarah Lawrence College, she continued her studies at the Art Students’ League and The National Academy of Design. Her work can be found in both private and public collections, including in the permanent collection of Greenwich Library’s Main Branch. Greenwich Magazine featured one of her paintings on its cover. Beyond drawing, painting, and printmaking, she also creates threedimensional art, making numerous screens and tiled and painted furniture. Her website is http://www.ilsegordon.com.

Ruthie Buell –

“Five Days, Five Nights”: A review

HOME > ARTICLE > BLOG > “FIVE DAYS, FIVE NIGHTS”: A REVIEW

EmailShare

BY:UNCLE RUTHIE BUELL| DECEMBER 4, 2020

“Five Days, Five Nights”: A review

It is always risky to construct an organic whole, a single all-inclusive meaning or, more boldly, a single metaphor for an entire book. But a larger definition leaps out at me. First, and most important, Five Days, Five Nights succeeds and does so beautifully, giving us exactly what the author intended — an almost perfect piece of fiction. I say “almost” not because I found fault, but because I am certain the author would use that word. Authors are always self-critical, even of that which they would consider completed.

I loved Five Days, Five Nights by Manuel Tiago, known to his Portuguese Communist companheiros as Álvaro Cunhal, long-time leader of the Portuguese Communist Party. I hung on every word. Indeed, on almost every page there was a cliff for just that purpose!

Cunhal wrote Five Days during an 11-year imprisonment in Forte de Peniche, from which he heroically escaped on January 3, 1960. He took with him a longer manuscript titled Até Amanhã, Camaradas (Until Tomorrow, Comrades) but left behind Five Days. When fascism ended in Portugal, the manuscript was returned to him, and he published it in 1975 under the pseudonym Manuel Tiago. The plot is described in People’s World:

Five Days, Five Nights is the fictional story of 19-year-old André and his attempt to flee to Spain from oppression in Portugal. To cross the border he enlists the help of the shady, dangerous, older criminal Lambaça. They must cross the rough border terrain, passing through villages and encountering a few peasants along their way.

I have to offer praise for the seamless translation by Eric A. Gordon, for it is hard to tell where where the Portuguese leaves off and the English begins, which may be the very definition of any really successful translation.

Five Days, Five Nights was a joy to read, and in a single reading at that (with a short lunch break). I see this work as a single subtle and well-crafted metaphor, political, yes, but much more. The words “poetic” and “poignant” come to mind.

The exact spot where I felt the story to be not just political, but comradely communistic, was in chapter 13 when the two main characters, Lambaça and André, take their leave of Zulmira, a beautiful country girl with whom they overnighted, who picks up a little extra money “working”: “The girl then said goodbye with her hand, in a gesture so sad and forlorn, that he would never stop thinking about it, nor ever stop feeling its pain.” (The edition issued by International Publishers also includes illustrations by Ilse Gordon, who lovingly captured this particular moment.)

The tale is, I believe, a metaphor for revolution. I see, in both plot and the personality of each character, that which is part of all revolutions. One quality common to revolutions, uncertainty, runs through the story. André cannot tell us exactly why he is on this journey or what his final destination will be. Also, he is young, as are all revolutions, hence the great degree of uncertainty, with much room for the maturation to come. Zulmira symbolizes the sadness of the oppression that must be overcome. And Lambaça holds within him both the nobility and the sometimes oppressive nature of revolution. We cringe at times at his gratuitous harshness and human flaws, but these are part of all revolutionaries. Please enlighten me, someone, if history has yet recorded a perfect revolution.

The novella ends with André about to enter a new country and a new life. We hope to meet him again and learn more about both him and revolution. And we will, because this is only Manuel Tiago’s, or Álvaro Cunhal’s, first novel to appear in English. A series of “Manuel Tiago” novels and stories are forthcoming from International Publishers, and we will meet many other characters who, like Lambaça and André, will pursue in their own ways the goal of overturning Portuguese fascism.

As a reader and lifelong political activist (I turned 90 this year!), I have to wonder why a man of such prominence in the Portuguese resistance would spend so much of his time writing fiction, but if Five Days, Five Nights is but the first sample of his writing accessible to English readers, with much more to come, I think I understand why.

Thanks to the efforts of the translator, I now not only have a new book but have met a new author, friend, and comrade. So may we all — that is my fervent hope.

A People’s World interview with the translator, Eric Gordon, can be read here.

Five Days, Five Nights

by Manuel Tiago (Álvaro Cunhal)

New York: International Publishers, 2020

Image: cyclingshepherd (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Michael Berkowitz –

Álvaro Cunhal had a little secret. It was a good thing that he did. Living under the fascist Salazar dictatorship of mid-20th-century Portugal for the first half of his life, Cunhal needed secrecy. After all, for decades he was a leader and ultimately the Secretary General of the Portuguese Communist Party, which waged a life-and-death struggle against the fascist regime.

So, Álvaro Cunhal was forced to go underground into hiding. After he was caught, he was imprisoned for 11 years, eight of them in solitary confinement. He was routinely tortured and starved. After his daring 1960 escape from Forte de Peniche Prison, this revolutionary was driven into exile from his native land, where he served the cause from abroad. He returned in 1974 after the revolution that finally, after almost half a century, overturned fascism, and that immediately led to the independence of the Portuguese colonies.

Once again, he became politically active in his native country, a public figure never to be ignored or forgotten. When he died at 91 in 2005, half a million people crowded the streets of Lisbon to celebrate his life.

Most of those celebrants could probably tell you something of his daring adventures, of how he devoted his life to the service of the Portuguese people. But very few knew Cunhal’s secret—Manuel Tiago!

It turned out that Cunhal had used his prison time, and later his exile time and still later his freedom back home, quite well. Aside from his political writings, he had become an accomplished artist, a translator of Shakespeare and, under the pen name of Manuel Tiago, the author of nine books of fiction, one of which (the present book under review) was later adapted to film and another into a popular TV series. The authorship of Cunhal’s books was known only to Party leadership until much later in his life.

Clearly, a Communist who gave his life to the cause must have had a higher purpose in leaving the world such a body of fiction. Now, readers of English have their first opportunity to find out.

Thanks to the adept translation of Eric Gordon, cultural editor of People’s World, we now have Manuel Tiago’s Five Days, Five Nights. This novella had been preserved, left in the archives of Peniche Prison when Cunhal escaped. After the 1974 Revolution, the military officers who ran the prison handed the manuscript back to Cunhal, and it was published the following year.

Five Days, Five Nights is the fictional story of 19-year-old André and his attempt to flee to Spain from oppression in Portugal. To cross the border, he enlists the help of the shady, dangerous, older criminal Lambaça. They must cross the rough border terrain, passing through villages and encountering a few peasants along their way.

Cunhal etches his characters sparsely, but as sharply as the rugged landscape. André’s youthful optimism, high sense of morality and energy contrast with Lambaça’s evasive, secretive manners, perhaps cultivated as a response to the corrupt, fascist order. Their relationship is of constant mistrust, occasionally violently flaring to the surface. The plot is driven by this conflict which threatens the outcome of André’s flight from the country. Through such dramatic tension, we see the struggle of the old order against the promise of a new progressive age.

Yet Cunhal is a shrewd teller of his tale. If André is an impatient youth, is he perhaps too naïve and impetuous for his own good? And if Lambaça is so crude and immoral, why does he trouble to take this young rebel over the border at such risk?

“André…spoke of the importance of the crossing, of responsibilities, cooperation. Now he spoke with a calm, persuasive voice, and leaning forward, attempted to discern in Lambaça some expression or gesture.

“In the dark of the night, Lambaça, still as a stone, did not react. Only when André had finished did he say, his words drawling with contempt, ‘I’ve known all that for more than twenty years.’”

The neo-realist noir novella takes pains to detail aspects of the modest lives along the border. Hardscrabble border-runners, vulnerable prostitutes, herders and villagers comprise the repressed underclass of fascist Portugal. Cunhal purposely doesn’t set his characters in too specific a place or time. But clearly the border represents hope and the possibility of change.

Gordon, the translator, has done an admirable job bringing to life Cunhal’s words describing the border flight which now defines the status of more and more of the world’s at-risk population. The publication benefits immensely from the accompanying series of illustrations by the artist Ilse Gordon (the translator’s sister), whose drawings round out our impressions of the principals, lending them humanity while placing them firmly in the context of rural hinterlands.

The book also features an informative foreword, author, translator and illustrator biographies, a map of Portugal, and an unusual feature at the end, “Some Questions to Ponder and Discuss,” obviously meant to spur the reader’s inquiry into the deeper meanings of the story.

International Publishers has begun with Five Days, Five Nights, and further “Manuel Tiago” books are reportedly coming. This will be a progressively staged publishing event I, for one, will be most interested in following.

A vote of gratitude is owed to the Gordons for their success in realizing and broadcasting Álvaro Cunhal’s secret, the description of the struggle for change against an oppressive order—lessons hard learned and well expressed.

Camila Valle –

What We Recovered in the Revolution

Álvaro Cunhal’s Five Days, Five Nights

by Camila Valle

(Mar 01, 2021)

Camila Valle is an editor, translator, and writer. She is assistant editor of Monthly Review.

Manuel Tiago (Álvaro Cunhal), Five Days, Five Nights (New York: International Publishers, 2020), $15.99, 70 pages, paperback.

June 15, 2005, was declared a national day of mourning in Portugal. Álvaro Cunhal, leader of Portugal’s Communist Party for half a century and central figure of the 1974 Carnation Revolution, was gone. As the government stated in its decree:

Álvaro Cunhal was one of the great Portuguese political figures of the twentieth century. His renown before, during, and after April 25, 1974, remains inseparably tied to the recent history of Portugal, particularly his role in the resistance to the dictatorship and the sacrifices he stoically endured in clandestinity, prison, and exile.

Over the years, Álvaro Cunhal decisively marked Portuguese political life by the profound conviction with which he defended and fought for his ideals.1

Five hundred thousand people attended Cunhal’s funeral in Lisbon.

A prolific political writer, Cunhal revealed in 1994 that he had also written several novels under the pseudonym Manuel Tiago. One of these novels, Five Days, Five Nights, was only translated into and published in English in 2020. Arrested in 1949, Cunhal wrote the novella while imprisoned, but did not take the draft with him when he escaped in 1960. Like many things we leave behind for a chance at freedom—only to unexpectedly rediscover them in the course of struggle—the manuscript was returned to him following the revolution and published under his pseudonym in 1975.

Despite the tropes the book reproduces, Cunhal, this particular period of Portuguese history, and the translation into English remain important. In part because Five Days, Five Nights is devoid of the stilted political speechifying sometimes found in political fiction, the novella manages to capture the complexities, loneliness, and bravery of ordinary people, and highlights how we find ways to look out for one another despite the barriers erected by society.

Land as Metaphor

Cunhal does not give us a time period, context, or backstory. The book simply begins with the protagonist André—an almost-19-year-old from Lisbon from whose point of view the story is told—needing to urgently cross the border into Spain and a man named Lambaça hired to help him. A foil to urban, youthfully naive, and implicitly middle-class André (perhaps inspired by Cunhal himself, who spent the early years of António Salazar’s fascist Estado Novo in the Lisboan student movement), middle-aged Lambaça is “short and wizened, [with] a cheerless face of a strong brown color, accentuated by a thick growth of whiskers, a black brush mustache, and small, dark, attentive eyes.… He manifested…something arrogant, daring and insolent.”2 As the two, famished and exhausted, trek through thickets, valleys, and steep hills, their antagonism, often expressed as a battle of masculine bravado (André at one point even lies about having killed someone and carrying a gun), drives the plot as much as the migratory journey itself.

Along the way, André ponders the “doleful, peaceful townships” inhabited by “peasants of few words.” For him, the countryside and its people, particularly its women, become symbols of alienation and the frequent desolation of life: “the landscape…the same loneliness, the same sad, rounded hilltops and even, in the distance, that same big mountain, silent and commanding, spreading out and observing from afar.” Put another way, André is always asking himself, “What tragedy was hidden in that little peasant cottage a hundred meters away from a forgotten settlement in the mountains?”3

At the time Cunhal first wrote what would become Five Days, Five Nights, Portugal was immersed in a long and brutal dictatorship. It was the least developed country in Western Europe, with high levels of poverty and illiteracy, and deeply dependent on the country’s colonies of Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau, as well as on Portuguese migrant workers sending money back home. Nevertheless, it is striking to read, even in fiction, such attributions to Portuguese rurality. Almost two decades after Cunhal’s first draft, Portugal, including its countryside, would become one of the freest places in the world.

In the 1974 revolution, mass strikes, unions, workers’ councils, neighborhood commissions, cooperatives, cultural centers, agricultural reform, and occupations of workplaces, houses, and land bloomed. There were popular clinics, people’s tribunals, self-run newspapers and radio stations, and Paulo Freire-inspired education campaigns. The independence movements in the colonies formally overthrew the yoke of colonial Portugal. A golf club in the south of the country declared it was open to all except its former members.4 Portuguese peasants did not need pity; they were, along with their urban counterparts, principal agents of the revolutionary process in the making.

Women as Way Station

In Five Days, Five Nights, we first encounter both women and quotidian life when the two travelers spend the night in the deserted countryside, in the small house of some people Lambaça knows. The scene is carefully composed: a sleeping old woman propped on the table, a young woman sewing wordlessly, an old man telling stories, a scarred man who leads them to mounds of straw on which to sleep, a barking dog called Douro.

A few chapters and tortuous paths later, André and Lambaça return to the small house. This time, only the young woman is inside, and she becomes the novella’s only fleshed out character besides the two men. She is, importantly, also the only other character with a name: Zulmira. Despite this, Zulmira is thereafter described only in terms of purity, beauty, and passivity, often depicted rocking her baby. Lambaça is presented as the vigorous violator of Zulmira and her goodness: “aggressively shoving a stool up against the table, [Lambaça] grabbed the girl with grotesque animal power and…kissed her neck hungrily. The girl neither reacted nor showed surprise. While he kissed her, she looked at André, quiet and submissive.”5 We soon understand that Zulmira is a sex worker, although poorly paid, if at all—“pay what you think is right,” she says feebly to Lambaça the next morning. Even when Zulmira is portrayed as having a sexuality, it is forced upon her, not really hers.

Here, André and Lambaça are again supposed to be foils, but while the contrasting descriptions may be intended to illustrate opposing treatments of Zulmira, as well as women more generally, they are two sides of the same coin. Lambaça is slimy and grotesque, blatantly disrespecting Zulmira, but André (and perhaps Cunhal himself) equally strips her of agency. For André, Zulmira is reduced to mere symbol, the supposedly pitiful lives of peasant women becoming the story’s paternalistic narrative impetus to fight for a better world. André “thought about his life and the reasons why he found himself in those mountains. He comforted himself. In the end, he was dedicating his life, joining his weakness to the millions of other weaknesses, trying to prevent the existence of girls in his country with that kind of fate.”6 What is missing, of course, is the notion that Zulmira can fight for herself. Neither Lambaça nor André seem to recognize that without Zulmira’s labor—her cooking, cleaning, bed making, body—they would not have had the food, shelter, and intimacy that gave dignity to their difficult and dangerous journey.

Land and women fit together neatly as metaphor, as objects to be rescued. But the history of the Carnation Revolution is a different one; it is also a history of gender and sexual liberation. Feminist groups, such as the Women’s Democratic Movement, Women’s Liberation Movement, and the Union of Antifascist Revolutionary Women, proliferated. Strikes and protests for equal pay and legal equality were massive and reaped significant victories, including the right to vote and the legalization of divorce. At movie theaters, long lines formed to watch films with erotic scenes, such as Last Tango in Paris, which thousands of Spaniards crossed the border to see on weekends since it was forbidden in Spain.7

Housewives came out in 1975 into the streets to protest against the high cost of living and demonstrated at the entrances to the supermarkets against the increase in food prices. Women agricultural workers, living in shacks, demanded decent living conditions. This participation went far beyond the gesture of poking carnations into the muzzles of the [Armed Forces Movement] men’s guns on the morning of 25 April.

As Manuela Tavares recalls, women’s participation in the workers struggles had fairly recent precedents in the form of the “down tools” strikes of 1969, in favour of better working conditions and also in the demonstrations against the colonial war.8

Borders as Permeable

In the novella’s last chapter, André and Lambaça are eating together, the former trying to convince the latter to ration food for the rest of the journey. Amused, Lambaça reveals that they have already crossed the border: “So what did my friend expect? A wall at the frontier, huh? Or maybe a plaque?”9 Borders, it is clear, are not naturally occurring. Walls, checkpoints, and restrictions on movement are all human made.

As André indignantly attempts to settle accounts, Lambaça ignores him, despite having verbally bumped up the financial cost of the journey throughout the story. “Stay on this road,” he advises André. “Up ahead you’ll find the city. Right away, to the left, you’ll see the station. You don’t have to ask, you can’t miss it. Just buy a ticket to Madrid. Or wherever you want.” André persists, insistently asking how much he owes. Lambaça does not answer and heads up the road, walking away. For the first time in the book, we are presented with a “proper, paved road. There was something weird about finding such a road after several days of marching through desert mountains. That little highway announced the presence of both friend and foe, nourishment and danger, community and shock, all the excitement of life in human society.”10

Despite all the borders and divisions—of gender, nation, region, color, age, poverty—we keep us safe. As the revolutionary Portuguese poet José Carlos Ary dos Santos warned: “no one can close the doors that April opened!”11 A paved road remains ahead; Zulmiras to the front.

Notes

1. “Decreto n.º 11/2005,” Diário da República 118 (2005): 3905. Author’s translation.

2. Manuel Tiago, Five Days, Five Nights (New York: International Publishers, 2020), 4.

3. Tiago, Five Days, Five Nights, 8, 51, 57.

4. Bob Light, “Portugal 1974–5,” International Socialism 142 (2014).

5. Tiago, Five Days, Five Nights, 47.

6. Tiago, Five Days, Five Nights, 51–52.

7. Catarina Principe, “40 Years After the 1974 Portuguese Revolution” (Socialism Conference, Chicago, 2014), available at wearemany.org.

8. Raquel Varela, A People’s History of the Portuguese Revolution (London: Pluto, 2019), 98.

9. Tiago, Five Days, Five Nights, 56.

10. Tiago, Five Days, Five Nights, 58.

11. José Carlos Ary dos Santos, “As Portas Que Abril Abriu,” 1975. Author’s translation.

Deborah Zamorano –

Five Days Five Nights is a captivating novel. Tiago’s book depicts an accurate illustration of Portugal

around the 1930s. The meticulous description of the people the main character encountered

while crossing from Portugal to Spain gives the readers a precise idea of how people dressed and

how they acted in the small Portuguese villages.

The book provides essential information to situate the readers in relation to the author’s

background. Such information is both at the foreword and at the short biographical note on the

author after the story. Tiago is the pen name of Alvaro Cunhal. In 1961, Alvaro Cunhal was the

elected secretary general of the Portuguese Communist Party. Before that time, he was in prison

due to his political views. The manuscript of this book was found in the archives of the Forte

de Peniche, where Cunhal had been imprisoned. Cunhal had left it behind when he escaped on

January 3, 1960, although he did take with him the manuscript to another, much longer and more

specifically political novel, Até Amanhã, Camaradas. After the 25th of April 1974 Revolution

that brought an end to fascism in Portugal, the military officers in charge of the fort returned

the manuscript to Cunhal, and he published it in 1975 under the pseudonym Manuel Tiago,

with a fictitious indication that it had been found in the “author’s” papers after his death (an

explanation he also used for Até Amanhã, Camaradas). It was also turned into a movie in 1997

In the book, André, the main character, had to cross from Portugal to Spain illegally. His

narrative is realistic and comes from deep rooted emotions. An example of this is when Tiago

narrates Andrés’s fears and reactions during his crossing. This makes the reading absorbing and

compelling. André’s sigh of relief when he finally realizes he is in Spain could not have been

more sympathetic.

One of the book’s highlights is to show the readers the obstacles and sufferings people who

resisted fascism had to face at the time the novel takes place. The author was, as already said, a

member of the Portuguese Communist Party and thus was arrested for his political activism.

Tiago wrote this manuscript while in prison. Tiago’s outstanding and impeccable fiction writing

style surely must have made this manuscript be perceived as just an innocent story in the eyes of

the law authorities of the time. Otherwise, they would not have allowed him to write it in prison.

Another strength of the book is to show a politically persecuted person from a humanistic

perspective. In a time when people do not seem to have enough tolerance towards different

ideas, the story certainly makes the readers think about such a standpoint. In addition, one of

the author’s literary strong points is to make the reader figure out details of the story. This is

particularly the case of the characterization of Lambaça, the man who helped André cross the

border. His mysterious behavior, his lack of words, and the fear he provoked in André definitely

creates a great deal of curiosity in the readers. This is one of the reasons that makes the story

so engaging.

The translation done by Erick* Gordon accurately conveys the novel’s details. Gordon’s translation

was the first translation from Portuguese to English. It certainly helped keep the emotions

and reactions shown by the characters’ precise, reliable, and faithful to the Portuguese version.

In addition, the illustrations done by Ilse Gordon complement the verbal detail of the author.

This book is highly recommended for a variety of audiences. It is recommended for students,

authors, and anyone who researches about the fascist resistance in Portugal during the twentieth

century. It is also recommended for students of twentieth-century Portuguese studies, especially

because of the author’s background provided in the book. Furthermore, the book is an eye opener

for anyone who is in the humanities area and, quite frankly, for any human being. The book is a

lesson in humanity and tolerance. The book’s main teaching is that one should be able to see the

human being behind his/her political views. Tiago did it with excellence. Five Days Five Nights

is unquestionably a worth reading book.

Deborah Zamorano

University of Texas at El Paso

* The translator was Eric A. Gordon (ed.)